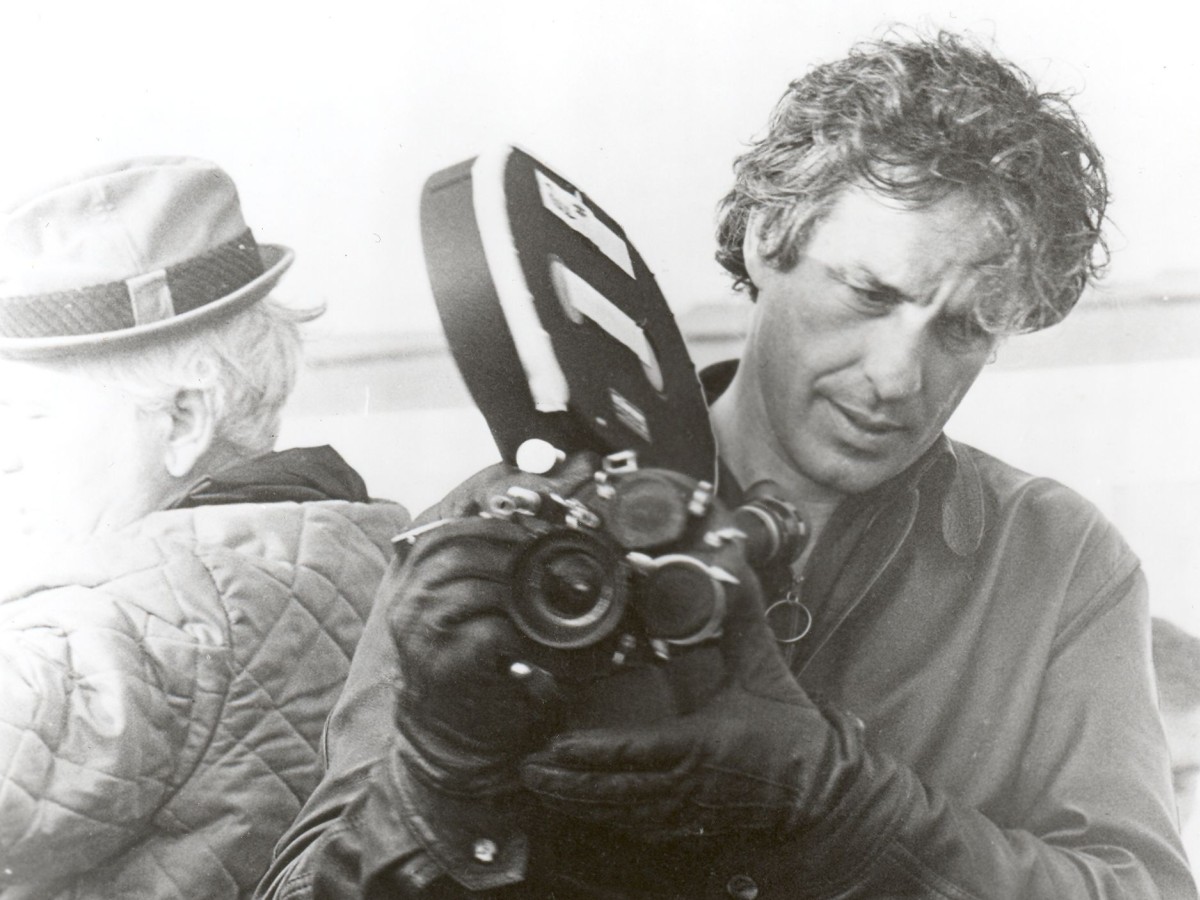

John Cassavetes

May 16 - June 8, 2008

“Directing really is a full-time hobby with me. I consider myself an amateur filmmaker.”

John Cassavetes, who was born in New York in 1929 to Greek immigrant parents and died in Los Angeles in 1989, remained a maverick throughout his life. In the American film industry he was tolerated more than he was respected; he had more standing as an actor than as a director; he was recognized by discerning film critics (especially in Europe), but was considered "difficult" even by arthouse audiences. Shortly after his death, however, a new view quickly took hold among a new generation of critics, film historians and audiences, namely, that the self-described "amateur filmmaker" John Cassavetes was arguably the most important American director since the demise of the studio system. Moreover, that his cinema of bodies, faces, and emotional intensities – a "documentary recording of fiction in the moment of its creation" (Ulrich Gregor) – marks a decisive fault line in post-1968 cinema after 1968.

15 years after the large Retrospective organized by Vienna's Stadtkino and the Vienna International Film Festival, which (together with the simultaneously published book by Andrea Lang and Bernhard Seiter and a follow-up tour of the films through Germany) played a major part in the international re-evaluation of Cassavetes, the Film Museum is once again showing all twelve of the director's features, contextualized by a research seminar and four lectures on John Cassevetes' work. The seminar and lectures are conceived by the Film Studies department (TFM) at the University of Vienna.

Cassavetes' directorial début, Shadows, which was released in two different versions in 1958 and 1959, had its origins in an actors workshop which he had initiated in 1956. The film was created in the streets of New York, was partially improvised and joined in its sensibility the hip cultures of jazz and beat literature. Its independence from conventional narrative and production modes became a signal for the New American Cinema. Today, the film, like its director, serves as a founding myth for “Indie” cinema in the U.S. It was to take a further ten years, however, before Cassavetes was actually able to establish a feasible model of film production outside of Hollywood. The intervening period was marked by two only partially successful films made within the industry, several works for TV and well-paid acting assignments, as well as an extreme three-year phase of completing his "second début": Faces (1965-68) was a new beginning, for the filmmaker and for narrative film in general.

Facesand the following seven masterpieces – from Husbands (1970) to Love Streams (1984) – are based on a conception of cinema which originates entirely with the actor as a living, real person. The actors are co-authors of all the humour and bitterness, pain and resiliency, the condition humaine which can be experienced in Cassavetes' films. They are, in the truest sense of the word, his "family", consisting of actual and "adopted" family members, including Gena Rowlands (his wife from 1954 on), Ben Gazzara, Peter Falk, Seymour Cassel and Cassavetes himself. "There's no such thing as a 'good actor'," Cassavetes used to say, "acting is just an extension of life", with all of its gaps and "mistakes", stumbles, cries and whispers.

Cassavetes' films present us with gentle vagabonds and overwrought husbands, desperate middle-class folk, semi-gangsters and actors at breaking point, "always on the fringe, somewhere between the tragic and the grotesque, between cruelty and sympathy, between violence and tenderness; a slight change of atmosphere, and one's watching a completely different film, sort of like looking into a mirror" (Georg Seeßlen). What makes the experience so intense, writes Anja Streiter, is "the degree of manual, mental and emotional work. Not hardware or software, but wetware. Blood, sweat and tears, guts and nerves, love, hope, ideals. It's almost like 19th-century art. Humanistic to the core, romantic, individualistic. This is exactly what made it so disconcerting for Americans of the time."