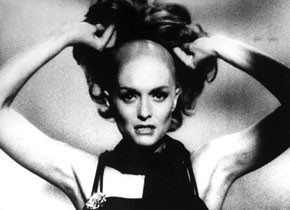

Samuel Fuller

The Complete Works

February 4 to March 2, 2006

The American director Samuel Fuller (1912-1997) is one of the legendary figures of cinema. One of the "Great Primitives" and a stylist of extravagant sensationalism, he became an icon of independence in the studio system.

His equally blunt manner confirmed this impression. One of Fuller's many small roles in films made by his admirers (the list goes from Steven Spielberg to the Kaurismäki brothers) provided the motto for the reception of his works.

In the middle of a wild party scene in Jean-Luc Godard's Pierrot le fou, Fuller pronounces: “Film is like a battleground. Love, hate, violence, action, death. In one word: emotion.”

Despite his lasting influence, Samuel Fuller's films are rarely shown in Europe today. In February, the Austrian Film Museum will present a complete Retrospective of his cinematic oeuvre for the first time in this country. Viewers will be able to discover the chaotic power of Fuller’s "film fist" as well as his thoroughly iconoclastic worldview.

His films deliver a history of the USA after 1945 that is as discerning as it is hysterical. Virtually no other artist comes to mind who was able to squeeze so much political content into the genre film triangle of action-machismo-melodrama.

The ideas in Fuller's films are inseparably connected to his biography. He was one of the last Hollywood directors who had "seen a lot of life" before starting a film career. The two decisive phases of his life, before he made his directorial début with the unconventional Western I Shot Jesse James (1949), were the time he spent in the newspaper business in New York, and the years on the African and European fronts in Word War II.

They also form the autobiographical underpinning for two of his greatest films which frame the beginning and end of his oeuvre. There is Fuller's favourite film, the self-financed Park Row (1952, an enthusiastic tribute to the New York "Newspaper Street" of the 1880s), which can also be seen as a "war film" - a battle between circulation figures and the truth; and on the other end, there is his brilliant opus magnum, the “real war” movie The Big Red One (1980), which is also an encyclopedic report on his front line experiences, right down to the detailed shot of the toilet paper roll on D-Day, which had to be got to land, intact and dry, no matter how.

Fuller's confrontational cinema is always in extremis, and it is between the extremes of his style, from the montage-staccato to the outrageous angles to the pulp-novel dialogue, that a simultaneously lyrical and brutal exploration of the critical spots in the American self-image can be found. Drastic contrasts aren't smoothed out; Fuller goes out of his way to look for them.

His obsession with both the pursuit of truth and the journalistic presentation of "hard-hitting facts" goes hand in hand with the desire for the maximum sensational effect possible. "From the first shot, you've got to grab the spectator by the balls and never let go again." Accordingly, he was in his element with the most extreme film format ? Cinemascope, which never recovered from House of Bamboo (1955) and Forty Guns (1957).

A dyed-in-the-wool American and a defender of the democratic ideas of the Founding Fathers, Fuller always attacked the bigotry of America from within the "heart of the empire", so to speak. This was true regardless of whether the films concerned conflicts in the "outside world", as in the magnificent Korean War films The Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets! (both 1951), or from "within". The intricate complexity of his literally high-tension concepts has remained unparalleled in popular American cinema to this day.

Social, political and ethnic conflicts blaze inextinguishably in his major works such as Pickup on South Street (1953), Run of the Arrow (1957), The Crimson Kimono (1959), The Naked Kiss (1964) and White Dog (1982, although, typically enough, it was suppressed in the U.S. at the time). Attacked both as a rabid anti-communist and as a leftist radical, Fuller never subscribed to any one ideology. His portrait of the USA as a madhouse in his most lurid masterpiece Shock Corridor (1963) is downright emblematic. Fuller remained true only to himself, and to his unswerving belief in freedom.