January 7 to February 9, 2012

During his lifetime, Giuseppe De Santis' master student, Elio Petri, was far better received abroad than at home: the leading Italian intellectuals of the new left did not know what to make of his baroque-sardonic, Pop Art vision of Brecht’s “theatre of the people” – even as Petri remained so close to them politically, as a scourge of the Christian Democrats. After his death, many of these writers confessed: we were wrong, we had blinders on; he was one of the greatest Italian filmmakers of the 1960s and 70s.

Like De Santis, Elio Petri came from humble beginnings: born in Rome in 1929, he grew up as the son of a coppersmith in a working-class suburb. He was politicized early, joined the Communist Party and worked for their youth organization, wrote for L'unita and Gioventù nuova. After the Hungarian uprising, however, he kept his distance from all PCI organizations. During those years Petri also met De Santis, and handed him a wonderful piece of material, the story for Roma ore 11 (1952). He became De Santis' most important artistic collaborator and co-writer of the screenplays for Un marito per Anna Zaccheo (1953), Giorni d’amore (1954), Uomini e lupi (1957), La strada lunga un anno (1958) and La Garçonnière (1960). Petri also wrote scripts for other filmmakers such as Carlo Lizzani and Gianni Puccini, but as he said later, the man from whom he learned everything about cinema, and life, was Giuseppe De Santis.

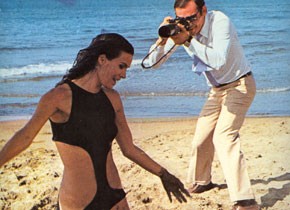

As early as 1954, Elio Petri directed his first short documentary, Nasce un campione, but it took another seven years before he was able to complete his feature film debut, L'assassino (1961), with Marcello Mastroianni in the title role. The film indicated the direction in which Petri would develop – grim, penetrating considerations of society in genre form. Not that he necessarily wanted to go there: in his little-known masterpiece I giorni contati (1963), Petri used a very different aesthetic register – something like "existential realism". However, starting with his fourth film, the Science-Fiction allegory La decima vittima (The Tenth Victim, 1965, again starring Mastroianni), Petri remained faithful to genre cinema.

This tendency reveals itself even in Petri's realistic narratives such as La classe operaia va in paradiso (1971), which he imbued with the fury and energetic mise-en-scène of his thrillers – Italy portrayed as a nightmare that made even the most seemingly paranoid fantasy seem like an exercise in cinema vérité. In Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto (1970), a high-ranking police officer murders his lover and leaves behind a crime scene full of clues – with little doubt about the killer's identity – just to see if his colleagues will dare to accuse him. Gian Maria Volonte shines in both films; he was Petri's favorite actor next to Mastroianni.

In one of Petri’s major works, the two actors appeared together: Todo modo (1976). Among the most radical Italian films of the decade, Todo modo was an allegory about the Gladio conspiracy, Gladio being the code name for a reputedly NATO-backed anti-communist organization with ties to the neo-fascist lodge P2. Petri obviously knew what he was talking about: The filmwas released just as this entire network of organized crime and fascist elements in the armed forces became publicly known... By this time, Petri had developed into a kind of public enemy; attempts were made to neutralize him and remove the film from Italian movie theaters. Before his untimely death in 1982, he was only able to direct one more feature film, the uncannily “soft” Le buone notizie – and a television adaptation of Sartre's "Dirty Hands": Petri's reckoning with the legacy of Stalinism.

The retrospective is organized in collaboration with Cinecittà Luce and the Italian Cultural Institute.