Hot on Cool

TV Between Show and Fourth Estate

November 6 to 27, 2025

"We don't deal in images; we deal in reality," noted Edward Bernays, Viennese by birth, nephew of Freud, and author of the 1928 book Propaganda. 70 years of television in Austria offers an opportunity to reflect on the development of a mass medium which in the second half of the 20th century was the defining medium to represent and shape society and still is today in many countries, even as clear changes in its current digital existence have emerged over the past decades. Next to avant-garde film, which like fine arts, has reflected aspects of the powerful space of public television, it was feature films with their narrative options which interpreted this part of our meta-universe, of indirect technological seeing. 'With cinema, the spectator is attracted by the image, with television, the spectator is projected by the image,' Jean-Luc Godard succinctly and logically differentiates the two media in Histoire(s) du cinéma. It is precisely the perspective of one mass medium on another, their mutual reflection, that opens up productive differences between their specificities – in McLuhan's sense, a "hot" medium thinks about a "cold" medium.

Every part of society placed different demands on the medium of TV, just as different standards must be used to evaluate privately owned U.S. networks and European public broadcasters. One should also recall that certain aspects of television were inherited from early cinema: views of foreign countries and spectacular and political incidents were first turned into major events in traveling movie shows and newsreels. The tube therefore oscillates between entertainment and scandal, information and manipulation, as well as between potential Fourth Estate and propaganda. In any case, it is certain that our current discourses about fake news versus facts in the face of a "social" media landslide are not new phenomena, but instead recall that these problems of perception already existed in mass communication when the first media appeared and there were still clear differences between sender and receiver.

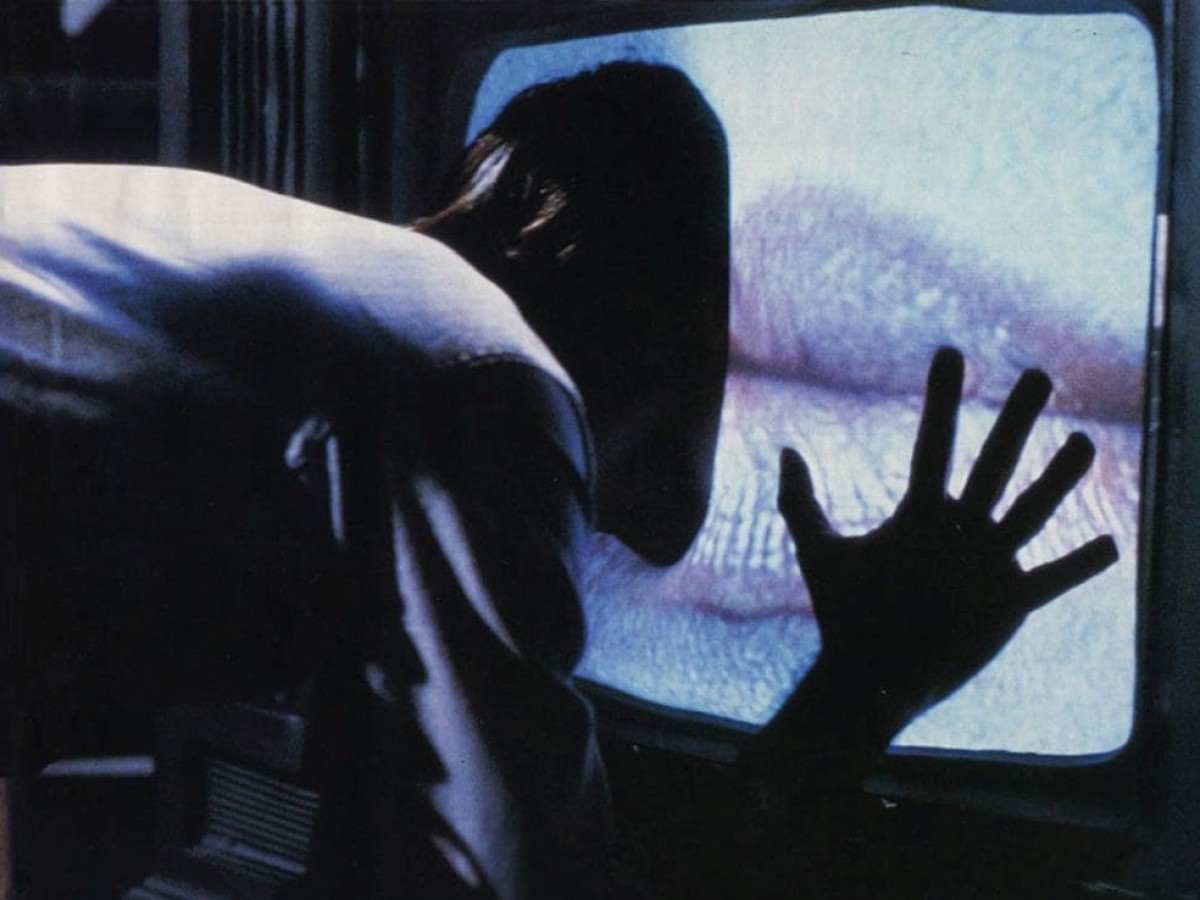

Alongside a special focus on Robert Sheckley's visionary short story The Price of Peril, adapted in two films by Tom Toelle and Yves Boisset which anticipate reality TV, other works show domains such as political reportage (Haskell Wexler, Nathanial Gutman), sensation and voyeurism (Bertrand Tavernier, Michael Haneke), star moderators on American programs (Sidney Lumet), and TV's dreamworld (Hal Ashby, David Cronenberg, Claude Chabrol and Peter Weir), in addition to the collective entertainment phenomenon of quiz shows (Robert Redford), investigative journalism (James Bridges), and aspects of the Fourth Estate (George Clooney).

Günther Anders pointedly stated: "We are inverted utopians: While utopians are those who cannot produce what they imagine, we cannot imagine what we produce." (Günther Selichar, Kurator / Translation: Ted Fendt)

Günther Selichar would like to thank Christoph Huber, Jurij Meden, and Loredana Selichar for their valuable input.

Introductions by Günther Selichar and Christoph Huber at selected screenings. Two discussion rounds complement the film program.

"We don't deal in images; we deal in reality," noted Edward Bernays, Viennese by birth, nephew of Freud, and author of the 1928 book Propaganda. 70 years of television in Austria offers an opportunity to reflect on the development of a mass medium which in the second half of the 20th century was the defining medium to represent and shape society and still is today in many countries, even as clear changes in its current digital existence have emerged over the past decades. Next to avant-garde film, which like fine arts, has reflected aspects of the powerful space of public television, it was feature films with their narrative options which interpreted this part of our meta-universe, of indirect technological seeing. 'With cinema, the spectator is attracted by the image, with television, the spectator is projected by the image,' Jean-Luc Godard succinctly and logically differentiates the two media in Histoire(s) du cinéma. It is precisely the perspective of one mass medium on another, their mutual reflection, that opens up productive differences between their specificities – in McLuhan's sense, a "hot" medium thinks about a "cold" medium.

Every part of society placed different demands on the medium of TV, just as different standards must be used to evaluate privately owned U.S. networks and European public broadcasters. One should also recall that certain aspects of television were inherited from early cinema: views of foreign countries and spectacular and political incidents were first turned into major events in traveling movie shows and newsreels. The tube therefore oscillates between entertainment and scandal, information and manipulation, as well as between potential Fourth Estate and propaganda. In any case, it is certain that our current discourses about fake news versus facts in the face of a "social" media landslide are not new phenomena, but instead recall that these problems of perception already existed in mass communication when the first media appeared and there were still clear differences between sender and receiver.

Alongside a special focus on Robert Sheckley's visionary short story The Price of Peril, adapted in two films by Tom Toelle and Yves Boisset which anticipate reality TV, other works show domains such as political reportage (Haskell Wexler, Nathanial Gutman), sensation and voyeurism (Bertrand Tavernier, Michael Haneke), star moderators on American programs (Sidney Lumet), and TV's dreamworld (Hal Ashby, David Cronenberg, Claude Chabrol and Peter Weir), in addition to the collective entertainment phenomenon of quiz shows (Robert Redford), investigative journalism (James Bridges), and aspects of the Fourth Estate (George Clooney).

Günther Anders pointedly stated: "We are inverted utopians: While utopians are those who cannot produce what they imagine, we cannot imagine what we produce." (Günther Selichar, Kurator / Translation: Ted Fendt)

Günther Selichar would like to thank Christoph Huber, Jurij Meden, and Loredana Selichar for their valuable input.

Introductions by Günther Selichar and Christoph Huber at selected screenings. Two discussion rounds complement the film program.

Related materials

Photos 2025 - "Hot on Cool"